Sweating rooftops

Researchers from ETH Zurich make roofs sweat: a newly developed synthetic mat for roofs could one day help to cool down buildings without using up electricity.

Sweating is a conceivably simple and efficient process for cooling down the body. People and animals use it to avoid overheating in midsummer temperatures or after physical exertion. The process is now also to be used to cool buildings. Researchers from Wendelin Stark’s group, a professor at the Institute for Chemical and Bioengineering, have developed a mat with which they are looking to cover roofs. If it rains, the mat soaks up water like a sponge. If the mat becomes warm in the sunshine, it releases water at its surface – it “sweats”. This extracts heat from the building and works in the same way as in us humans: when we perspire, glands in our skin secrete sweat, which gradually evaporates. For a bead of sweat to turn into vapour, it needs energy, which it extracts from the body in the form of heat.

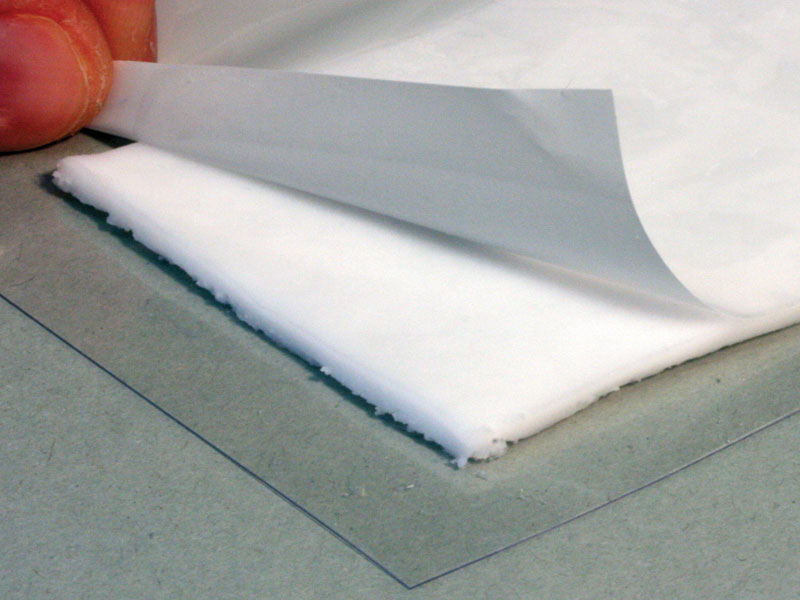

For the sweating mats, the researchers used a special polymer, abbreviated to PNIPAM, which is protected by a water-permeable membrane. The mat can thus fill with water when it rains. PNIPAM’s storage capacity is temperature-dependent. If the material becomes warmer than thirty-two degrees in direct sunlight, it shrinks up and adopts hydrophobic properties. This forces the water through the membrane to the surface of the mat, where is evaporates like sweat on our skin.

Tests with model houses

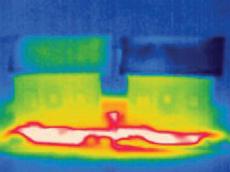

The researchers tested the principle on a small scale: they covered the roofs of model railway buildings with five-millimetre-thick mats, shone a special lamp that imitates sunlight in our climes onto them and measured the temperature inside the miniature houses.

Compared to a mat filled with a conventional polymer that does not shrink up in heat, the cooling capability of the PNIPAM mat was considerably greater. “The house insulated with the PNIPAM mat warmed up much more slowly,” says ETH-Zurich doctoral student Aline Rotzetter, first author of the corresponding original publication in the journal Advanced Materials. While a mat with a conventional polymer is comparable to a normal sponge, PNIPAM mats selectively give off water when heated up.

Less electricity for air-conditioning system

Buildings covered with such mats should need to be cooled less with air-conditioning systems in high temperatures. According to calculations by the ETH-Zurich scientists, a mat only a few millimetres thick could already save up to sixty per cent of the energy expended for air conditioning in strong sunshine in July.

The step up from a model house to a real building, however, is still a long way off. First, a series of open questions needs to be clarified, such as whether the evaporation mats are also frost-resistant, says Rotzetter. As the cooling method has now been published in a journal and is not patented, anyone is free to seize upon it and hone it for the market. “Our sweating mats are just the ticket for developing and emerging countries in warm regions of the world, too, as the system is also very inexpensive.”

Literature reference

Rotzetter

ACC, Schumacher CM, Bubenhofer SB, Grass RN, Gerber LC, Zeltner M, Stark WJ:

Thermoresponsive Polymer Induced Sweating Surfaces as an Efficient Way to

Passively Cool Buildings. Advanced Materials, 2012, advance online publication,

DOI: 10.1002/adma.201202574

READER COMMENTS