Through the eyes of a European woman

It is impossible for a woman to leave the premises of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) as a European. First of all it is necessary to cover jeans and T shirt with the traditional Islamic gown, the abaya, and exchange the self-image gained in Europe for Arab customs.

You hear all sorts of horror stories about the kind of life women in Saudi Arabia have: women do not hold a passport. If they want to travel, their husbands or fathers have to grant them permission. If a woman is wronged by a man then she has to painstakingly prove it before the culprit is held to account. Women are only allowed to work – if at all – under difficult conditions. In short: Saudi Arabian women in general have no say in their country.

Practical considerations

My personal concerns about the Kingdom were of a more practical kind: how do women get from A to B, if they are neither allowed to drive a car nor be seen in public together with an unfamiliar man, i.e. a non-relative? Can I wear flip-flops and a T‑shirt, or do I have to wear an abaya over the top – the pitch black, all covering, full-length gown? Do I have to wear a veil? Can I ride a bike? How will my emancipated ego react if local men ignore me when I speak to or greet them?

Luckily the KAUST campus is a sharia-free zone that is out of bounds for the moral police, which are otherwise omnipresent in the country and make sure that people behave in a religiously correct manner. People are free to choose how they dress, although it should not “expose anything”. Women are allowed to drive to the supermarket on campus. And, much more importantly, although it seems so normal for us Europeans that we hardly notice it: men and women are allowed to study, work, eat lunch and participate in sports together or simply just spend time with each other. All other educational institutions and workplaces in the Kingdom are strictly separated according to sex. Girls’ schools are taught exclusively by women teachers, and women study and work in separate lecture theatres or offices.

The bathing problem

For several weeks the campus residents have also had access to a beach and swimming pools. This has happened after a considerable delay, as for a long time people did not know what the general conditions for use should be, i.e. whether men and women should bathe separately or together. Stories of wild student beach parties could spread through the country like wildfire and would fan the flames of KAUST’s conservative critics, of which there are more than enough: many deeply religious scholars, lawyers and teachers see the joint education of young people as a decline in values, but they have to accept the King’s project, albeit grudgingly.

In the end it was announced that women have to wear one-piece swimsuits and the pools have to be divided according to sex. Hardly anyone keeps to the first rule, and the second one was revoked even before the pools were opened, as the professors complained that they would not be able to take their two-year-old daughters swimming! Now the following consensus has been reached: the small pool is for women only, and the large pool is for families and during certain times just for men.

The Western female staff on campus generally give me positive feedback: the Arab men respect their female colleagues, even though long-trained reflexes, which have been passed on since infancy, still sometimes come to the fore. However, these are stifled straight away and an apology offered.

There are, however, also unpleasant things on campus: everywhere they go women are always stared at and watched without shame. Not just by Arabs, but also by the immigrant workers from India, Pakistan and South-East Asia, who are currently helping with the construction of the infrastructure. Even though I try to ignore it, sometimes it can be terribly annoying. And in queues men are often served first, which drives me round the bend.

When I pass the large gate linking the campus to the outside world, I have to fully conform to the local customs and practices. I dutifully sit in the rear seat of the car, do not look men in the eye and wear my abaya with a denim (!) trim, which I picked up at the market at a bargain price.

Western women have a bad reputation

In spite of this I am still stared at, sometimes beeped at and even, albeit rarely, groped. In liberal Jeddah on the west coast of Saudi Arabia, women are thankfully allowed to leave their head uncovered, although people can then see my European origins from a distance. For the locals Western women are seen as easy prey, as permissive, corrupted beings. My abaya, which is slightly too short and reveals some of my ankle, increases this perception.

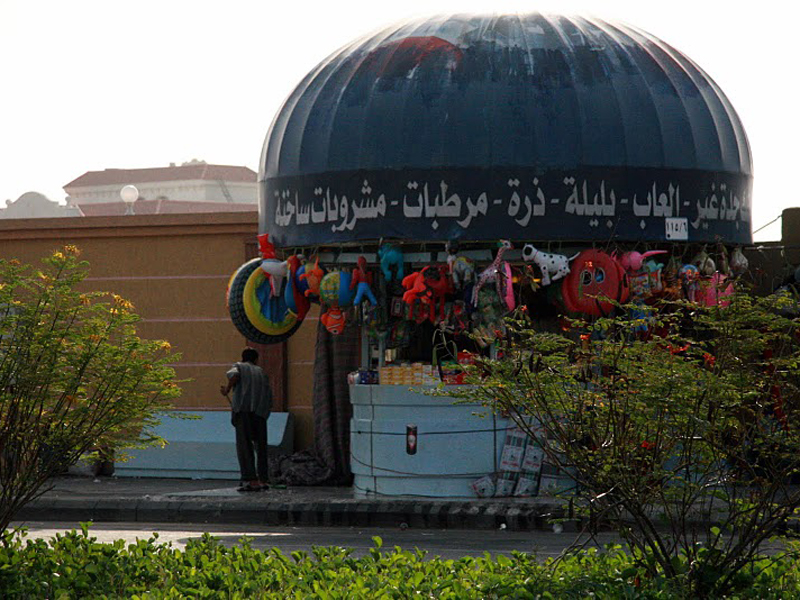

But the few times I was in Jeddah, I felt safe and well. Often you hear people saying that women should never go out alone, but I think I could walk through any of the back streets of the Souk (or Al‑Balad, as the old town in Jeddah is called) without a problem. With a few exceptions the tradesmen are friendly, and if you are unsure about something someone will definitely help you.

Apart from the heat, which builds up under the thick, black cloth of the abaya (and this is always the case), I have got used to my new going-out dress very quickly. It does actually have its advantages: you don’t have to worry about what to wear underneath, you don’t have to pull your stomach in all the time and your legs have a lot of freedom. However: why are men allowed to run around in these wonderful white outfits while women get a black cloak? Excuse me – how symbolic is that? And it gets even worse: due to the total concealment, women lose all their human traits and become just a black bag with feet. It is as if their humanity is taken away and they become an object, which therefore earns less respect!

For men, on the other hand, the white clothing is not mandatory. They are free to choose between Western and Arab clothing. I am actually a fan of traditional clothing, as it brings a bit of variation to our globalised fashion style and underlines peoples’ cultural origin. But I would never be able to accept the fact that women have to be strictly concealed at temperatures of 30-40 degrees Celsius and with the crushing air humidity, while men are allowed to walk alongside their mummified wives in Bermuda shorts and sleeveless shirts.

In general it is more pleasant to live here than I could have dreamt two months ago in cold Zurich. It is, of course, the done thing for Westerners to moan about abayas and the driving ban. But you get used to the new lifestyle surprisingly quickly. Thanks to the relaxed campus rules I can get to know the other side of Saudi Arabia in severely diluted concentrations. And last but not least, the knowledge that I have my return ticket in my drawer helps me to overcome the unpleasantness and to enjoy the good times more!

About the author

Sabrina Metzger studied interdisciplinary

sciences at ETH Zurich. After working on a project at the Swiss Seismological

Service for a year, which involved analyzing the micro-earthquake near the

Gotthard Basis Tunnel still under construction, she then moved to Spectraseis

Technologie AG, a spin-off of Zurich University. In the spring of 2008, she

returned to ETH Zurich to embark on a PhD at the Institute for Geophysics.

Metzger

is currently in Saudi Arabia, however, working as a guest researcher at

the

recently founded King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

(KAUST).

This is because her supervisor, the Icelandic geophysicist Sigurjón

Jónsson,

moved to KAUST from ETH Zurich to take up a position as an associate

professor.

READER COMMENTS