Maloja is ready to start

It is built in sparkling white and with a striking similarity to a real Formula 1 racer, but just a little bit smaller. Students of mechanical engineering at the D-MAVT recently unveiled their Formula student racer called “Maloja”. Its preceding model “Albula” was present, too - converted into a hybrid racing car. In addition, a free-kick robot and a four-legged walking robot were presented.

The suspense was enormous. A red silk cloth covered the announced new Formula student racing car, and only its outline suggested that “Maloja” would somehow look similar to its predecessor “Albula” which, after reconstruction and the instillation of a hybrid engine, had been presented only a few moments before. Amid the applause of the audience the members of the 23-strong team pulled the silk cloth away, presenting the sparkling white racing car in the spotlight.

Carbon saves weight

“Maloja” resembles its predecessor “Albula”, but the students have added numerous innovations. The monocoque, the seat shell, the steering wheel, the side pods, and the A-arms are now made of carbon. The undertray has been aerodynamically optimized and consists of carbon, too. The rims and wheels are bigger and the pilot has more room in the cockpit, which, in addition, contains more user-friendly electronics.

The construction of the engine is comparable with the previous model, but air intake has been optimized. The 600 cubic centimeters capacity engine is an integrated, supporting unit. “Maloja” has a set of four brakes whereas “Albula” only had three. Thanks to the consistent use of carbon parts, among the other improvements, the new racing car has a total weight of 200 kilograms and is therefore one sixth lighter than the previous model.

35,000 man-hours

Thanks to its lower weight the car is nippier than its predecessor and can accelerate from zero to 100 km/h in 3.7 seconds. It has 90 hp and reaches a maximum speed of 120 km/h. Just like last year the group of students will participate in a series of races in Silverstone, Hockenheim, and in Maranello, Italy. The first competition will already take place in a few days’ time. It will not in the first place be a matter of speed only. A business plan for the future, which has to comprise a marketing strategy for the sale of 1000 vehicles at a price of below 25,000 franks, will be taken into consideration, too. Additional criteria are various test, among them an endurance test.

The students have invested around 35’000 hours in the construction of the vehicle. The “Maloja” project team included not only 15 mechanical engineering students from ETH Zurich but also two students of electrical engineering at the University of Applied Sciences in Lucerne, two students of economics at the University of St. Gallen and three design students from the Academy of Arts and Design HGK Zurich.

“Albula” is becoming eco-friendlier

“Albula” has not yet served its time. A second group of students converted last years’ racing car into a hybrid vehicle. It now contains an electric motor which is supported by a gas engine. Because the electric motor needs a battery of proportionate size, the car had to be adapted to quite a large extent. On the one hand the undertray was widened, on the other there was a need for a new braking system. It has around 150 hp. In July, the group will participate for the first time in a race in the hybrid vehicles category, on the Silverstone Formula 1 circuit.

At the beginning, the „Albula“ team consisted of six students, but as the complexity grew, new faces joined the team, so that in the end 15 students worked on the project.

Soccer robot beats national team goalkeeper

A third group occupied itself with another male domain: soccer. The “Bender” team of six consisting of four men and two women constructed an artificial free-kick device called “Bender”. In principle, this “David Beckham” robot is a box which is positioned at a free-kick distance to the goal. A computer simulation calculates the trajectory and the machine can be adjusted accordingly, so the ball flies at high speed and a lot of spin to the selected spot. The machine could help in the training of goalkeepers, practicing crosses, corner kicks, or free kicks.

At its first test the “Beckham” robot faltered as video recordings of the students showed. But after some optimization the prospective engineers could test it on the pitch: “Bender” faced former national team goalkeeper Jörg Stiel, who occasionally had to stretch so as not to get beaten by the robot.

From crawling to walking

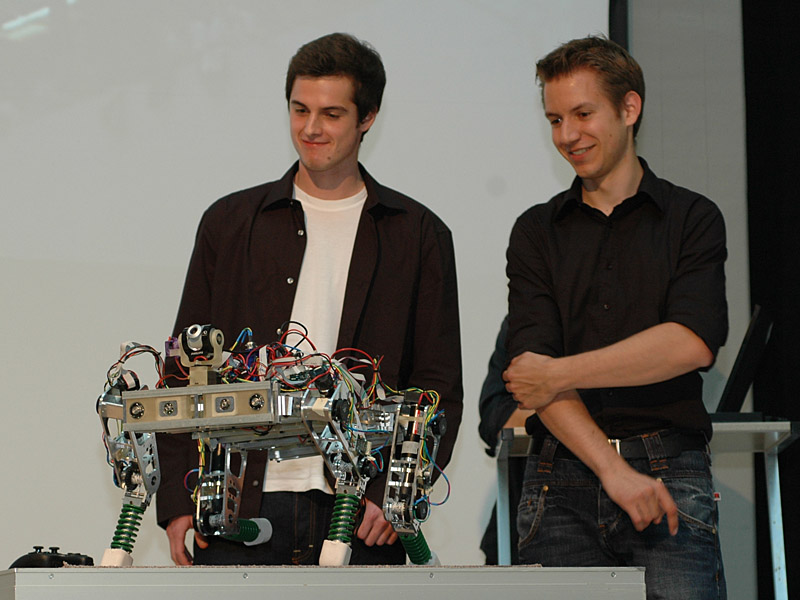

The fourth group did not quite achieve their target of turning “A.L.F”, a walking robot with suspension, into a soccer player. They started their focus project in order to participate in the Robocup, a soccer tournament for robots, in the United States. But the students failed to reach this target. The development of the walking robot took too long and the enterprise was more complicated than the students had imagined. After the conception and the assembly of the individual components the team had to teach the robot – just as you would with an infant - to stand up and walk, which was not easy. At the beginning, “A.L.F” was like a puppet on strings to relieve the weight on its legs. Video recordings showed how the robot had to learn slowly to use its legs correctly. All the same, tragicomic accidents happened over and over again.

“A.L.F.” presented itself with a cautious lethargic aspect. The students handled the robot like porcelain; after all it is worth 25,000 francs. All the same, the students have achieved a remarkable feat. At the rollout “A.L.F.” moved its legs slowly, but coordinated.

Teamwork to the fore

It is not the aim of these focus projects to create a product ready for the market. During their Bachelor studies the students have to show how a project is converted from an initial idea into practice. Everyone starts at zero. They have to formulate an idea, then sketch it, construct it, provide the necessary fundamentals, draught it on CAD, assemble the machine and finally set it in motion.

In his speech, Professor Roland Siegwart emphasized that the implementation of such projects needs enthusiastic students. It is not the result that is judged but the way to the same. “Students learn to cooperate in a team and also to carry a project through”. This demands a great deal from the students. The project was limited to one year and especially the nights before the presentation were far too short for many of the students.

Luigi Guzzella, Professor at the ETH Zurich Measurement and Control Laboratory, added that “the projects are to convey a meaning”. A meaning which many can only realize once their product is in the spotlight.

READER COMMENTS