An irreplaceable treasure trove of data

150 years ago, ETH Zurich appointed the first full-time curator for the Zurich Herbarium, part of ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich. It contains more than three million specimens which today are priceless, especially for modern research.

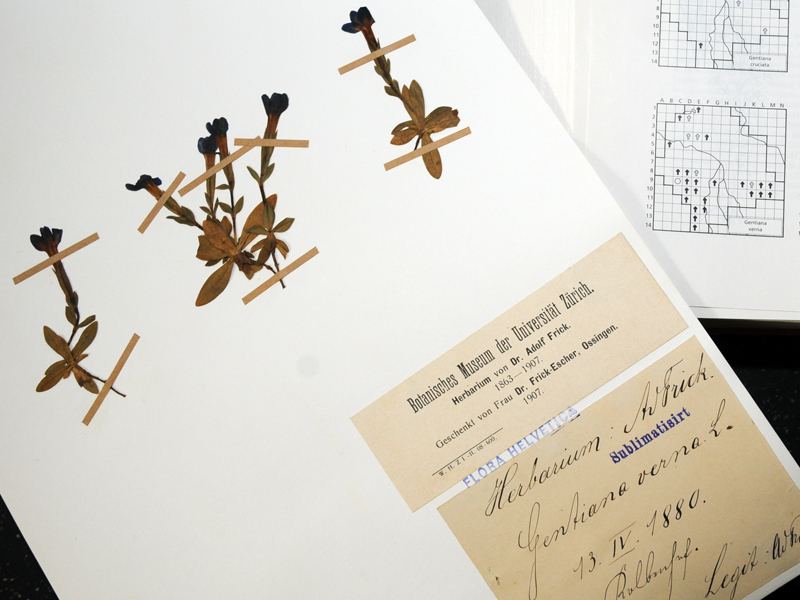

Matthias Baltisberger, curator of the Zurich Herbarium, part of ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich, stands in a meadow at the foot of the Üetliberg mountain near the district of Kolbenhof on the outskirts of Zurich. Dandelions bloom luxuriantly in the lush green grass. The 17-year-old amateur botanist Adolf Frick also climbed to this place one day in April 1880. The growth of grass then must have been sparse and scanty, with no trace of dandelions. Frick only needed to bend down to pick a couple of spring gentians and put them into his botanical specimen box. Back home, he dried and pressed the plants and glued them onto a sheet of paper with a concise inscription.

At that time, he could not imagine that Matthias Baltisberger would stand in the same meadow more than 120 years later, holding in his hand a specimen from his collection – with gentians that can no longer be found in downtown Zurich.

Preserving first-hand evidence

Frick’s living testimony to bygone days is carefully preserved in the botanical collection of the two higher education institutions, a collection which this year celebrates a birthday: the Herbarium was officially founded 150 years ago with the appointment of its first full-time curator, Christian Brügger. Baltisberger and the curator of the fungi collection, Reinhard Berndt, will celebrate this anniversary in the CHN Lichthof on 17 June. The fungi collection (cf ETH Life) is part of the Herbarium because fungi were originally regarded as plants. The fungi are kept in the CHN Building, ETH Zentrum, and the plants in the Botanical Garden of the University of Zurich.

The first curator 150 years ago

The founding collection of the Herbarium was furnished by Oswald Heer, Professor of Botany at the University of Zurich, who subsequently also held a double professorship at ETH Zurich. He collected plants because of his personal interest and also for teaching purposes, and his collection grew steadily until it became too large for him, which is why Brügger was appointed curator. This marked the start of an eventful history. The botanical institutes of ETH Zurich and the University separated in 1884, the Herbarium going to ETH Zurich and the zoology collections to the University. In 1895 the University founded the Botanical Museum at the new Institute of Systematic Botany, thus creating its own collection.

ETH Zurich and the University reunited their herbaria almost one hundred years later, thereby forming a collection that is among the 20 largest in the world, the stock having been constantly enlarged over the course of time through the addition of private collections, including 150,000 specimens from the Rübel Collection. The Zurich Herbarium is the second largest in Switzerland behind that owned by the Conservatoire et Jardin botanique of the City of Geneva. It contains 2.5 million plant specimens and one million fungus specimens.

Modern research with ancient materials

Many people associate the word “herbarium” with antiquated science and dusty old dried plants. Baltisberger says that this attitude is legitimate but has no connection with modern herbarium work. He states that, in the past, plants were collected mainly for documentation and comparison purposes. Collectors in the 19th century even traded plant specimens to earn money.

Now as before, the aim of the Herbarium is documentation. However, the Botany professor stresses that, “Today, we also use it to carry out modern biodiversity research.” One example is goldenrod, an invasive plant from North America: in the past, botanists often collected anything that was big, colorful and conspicuous, such as goldenrod. Herbarium specimens can now be used to demonstrate how the plant has spread geographically and over time.

The specimens also provide evidence of the spatial and temporal variability and morphology of a plant species. Researchers can trace back how the fertility of pollen has developed, or can isolate heavy metals from the tiniest samples of leaf. Even genetic material can be recovered from specimens up to 200 years old. Baltisberger is convinced that the Herbarium could also become of interest to climate researchers, because the specimens provide information about changes in the biology and distribution of species or types of vegetation.

Every specimen is unique

The characteristic features of a specimen are the species name, collection site, collection date and collector. Baltisberger stresses that “This makes every single one a highly valuable unique specimen. If it is destroyed, one cannot simply go outside and replace it with a plant of the same species.” The main reason for this is that every individual of a particular species is genetically unique.

The Zurich Herbarium also holds more than 13,000 type specimens. A type specimen is the plant on which the first description of a plant was based. If a researcher wants to describe a new species, he must compare it with type specimens. This is time-consuming work that is carried out in herbaria all over the world. Biosystematics experts have online access to information on the type specimens in the Zurich Herbarium, though they are not allowed to borrow type specimens of vascular plants – the specimens are too valuable for that.

Baltisberger feels that the Herbarium houses an enormous treasure trove of data. “It is a fundamental instrument, just as libraries are for linguists.” He says that it is important to continue to care for the collection, to update and enlarge it, and, above all, to work with it.

Protecting a cultural asset

To ensure collections are not lost, they need the same protection as other cultural assets. Specimens can be damaged by fire, water or insects. Were a war to break out, the Herbarium would have to be moved into a bunker. However, people who handle the material carelessly are a much more everyday danger. This is why curator Baltisberger issues only bound volumes, not individual specimens. “If an individual sheet were to be filed incorrectly, there is only a one in two and a half million chance of finding it again.”

READER COMMENTS